This post is a summary of the talk given by Dr Jayne Carroll from the Institute for Name-Studies (University of Nottingham) at the Staffordshire Record Office on 4th February 2017.

More information on the place-names mentioned in this post can be found on the Key to English Place-Names.

The English Place-Name Survey

Sir Frank Stenton. Copyright the artist’s estate / Bridgeman Art Library, photo credit University of Reading Art Collection

The English Place-Name Society (EPNS) was established in 1923 with the aim of producing a county-by-county survey of the place-names of England. The first volume, an Introduction to the Survey, was published in 1924, and the survey for Buckinghamshire, written by Allen Mawer and Frank Stenton, was released a year later.

The English Place-Name Survey now has 91 volumes, with most counties in England having at least partial coverage. The earliest counties to be surveyed consisted of only a single volume, but the most recent surveys have much more detailed coverage, several with more than six volumes so far completed. The most recent counties to be surveyed contain major place-names (the names of settlements and other large features) as well as minor names (smaller landscape features, street-names and buildings) and field-names.

Coverage of the English Place-Name Survey to date

A place-name originally served as a descriptive label, and therefore had meaning to the people who gave and used that name. In order to unlock that meaning, we have to establish which words were originally used to make up that name. A place-name survey, therefore, involves the collection of as many historical forms of a place-name as possible. The earliest forms of that name can then be used to work out the words it derives from and the meaning it has when it functioned as a label – in other words, etymological analysis. As well as working out a name’s literal meaning, it is then possible to think about the further significance a name might have had. It becomes an important piece of historical and linguistic evidence, and preserves the kind of information which may not be found in surviving historical documents.

For example, the modern form of the Shropshire place-name Broseley gives us no clue as to its original meaning, because it has transformed so significantly since the name was first coined. Our first source for the name, from 1177, gives the name as Burewardeslega, from which we can deduce that it comes from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) words burh-weard ‘fort-keeper’ and lēah ‘open woodland’. Broseley, therefore, means ‘open woodland of the fort-keeper’, or perhaps ‘open woodland of a man called Burgweard’.

Sources of place-names

Domesday Book (top), TNA E 31/2 (www.nationalarchives.org) and the name Blithfield, lined through, from opendomesday.org

Many names are first recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 – the survey conducted on behalf of William the Conqueror. Some names are recorded even earlier than this, in documents such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle or in wills and charters from the Anglo-Saxon period.

Names are also preserved in more unusual sources. Coins from the later Anglo-Saxon period, for example, recorded their place of minting. The name Stafford is preserved on a coin from the late tenth century (see image below): Stafford’s name comes from the Old English words stæð ‘landing place’ and ford. The first part of the name appears on the top-left of the coin.

Coin from the reign of Æthelred II, showing the name Stafford (STAEÐ) at the top-left. EMC 1017.0252 (reverse) (www-cm.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/emc)

Post-Conquest sources include documents such as Pipe Rolls and manorial Court Rolls, many of which are in Latin. Some of these are preserved in national repositories such as the National Archives, and others are held in local collections at county archives or universities. From the late medieval period there are often estate maps, terriers and surveys preserving place-names, and the Enclosure Awards and Tithe Apportionments of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries provide a wealth of minor names and field-names for many places in the country.

The languages of place-names

Place-names preserve a number of different languages which were spoken in what became England. Some names contain words in languages so old we know almost nothing about them! The first language we can talk about with confidence is Brittonic (which became Cornish, Welsh and Cumbric), which survives mostly in the names of landscape features, and more in the western part of the country than in the east.

With the coming of the Romans came Latin, and a few names preserve this language. Most surviving place-names, though, were coined in the Old English language of the Anglo-Saxon settlers. Some are in Old Norse, the language of the Scandinavian settlers of the ninth and tenth centuries – these are more common in the east of the country where Vikings are known to have settled.

With the Norman Conquest of 1066 came the French language. Because there were relatively few Norman incomers, and because almost all of them were in the higher echelons of society, they had little impact on the place-names of the country. There are a few names which were coined in French, but mostly the administrators continued to use the pre-existing place-names. Medieval Latin was used as the language of administration, and some parts of place-names derive from this language. This is the case with many affixes like magna and parva, meaning ‘great’ and ‘little’.

Of course, there are later forms of English preserved in place-names too, but they tend to be easier to decipher!

Signpost near Brewood, Staffordshire, 2009. Copyright Roger Kidd and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons License.

The Staffordshire signpost in the photograph illustrates just how varied the linguistic landscape of the county is. Britonnic words are found in Brewood (*bre is a word for ‘hill’) and Penkridge (*penno- ‘head, end’ and *crouco- ‘hill, tumulus).

Stafford, as we’ve already seen, is Old English, as is Wolverhampton, which preserves the name of an Anglo-Saxon woman, Wulfrun, along with the Old English words hēah ‘high’ and tūn ‘estate’. Codsall also contains the name of an Anglo-Saxon (*Cōd), along with the word halh, meaning ‘nook’.

Four Ashes is a more modern name, recorded in 1683.

More Britonnic (Celtic) names survive in Staffordshire than in some other parts of the country. In general, there is a tendency for a higher number of pre-English names to survive the further west in England you are. The river-name Trent is Britonnic, from the word *trisantonā, meaning ‘trespasser’. This metaphorical name shows that the Trent’s propensity to flood was just as important over 1000 years ago as it is today!

Flooding at Trent Lock in Nottinghamshire in 2012. Photograph by Brian Tyler on BBC News (www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-20839132)

There is evidence for other languages in Staffordshire too: Swinscoe is formed from two Old Norse words, svín ‘swine’ and skógr ‘wood’. Beaudesert is one of the few French names, meaning ‘beautiful wilderness’. In 1428 Great Barr was referred to as Magna Barra, containing Medieval Latin magna ‘great’.

What else do place-names tell us?

As well as evidence for different languages being used, place-names contain words referring to ownership of land. Kings and queens are found in Kingston and Queenborough. Prestwick refers to priests, and Monkton to monks. Norman families sometimes added their names to the places they owned, as is the case in Stoke Mandeville, and the lower ranks are represented in Charlton (from Old English ceorl ‘peasant’) and Threlkeld (from Old Norse þrǽll ‘serf, slave’).

Names can also mark places which were administratively important. Cuttlestone in Staffordshire is both the name of a hundred (an administrative district) and refers to a stone used as a meeting-place. Trees were also used as meeting-places, sometimes for large administrative areas: Skyrack in Yorkshire comes from the Old English scīr-āc ‘shire oak’.

Travel routes were marked by place-names too, with ferries (Ferriby), roads (Saltway), bridges (Cambridge), fords (Oxford) and landing-places (Stafford) all labelled. So too were some buildings and structures, with fortifications (Bury, from Old English burh ‘fortified place’), churches (Whitchurch) , pillars (Barnstaple, from Old English stapol ‘pillar, post’) and look-out places (Wardon).

References to industry and manufacturing can be found in settlement-names, with bakers in Baxterley and Baxenden, smiths in Smethwick, salt in Salterton and Seasalter, and milling in Millbrook and Milford. Soap-making is even marked in Sapperton.

Place-names also commemorate religion and folklore, with references to pre-Christian deities in Thundersley and Woodnesborough, and even dragons in Drakelow!

Crime and punishment features in Mortgrove and Morpeth, which both refer to murder (either literally or metaphorically), and gallows in Galphay and Gawber.

Place-names and the landscape

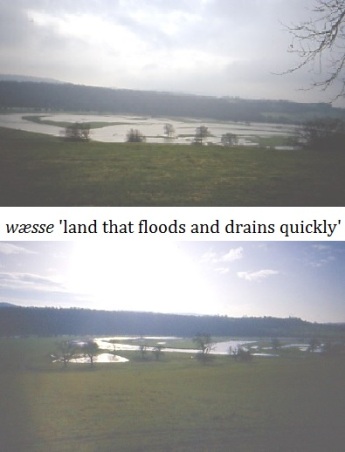

Flash flooding at Buildwas, Shropshire. The two photographs were taken only a day apart, with the water quickly subsiding. Photos by Margaret Gelling and Ann Cole, made available by the SNSBI (www.snsbi.org.uk/Gelling-Cole_photos.html)

Many place-names contain words that describe the landscape. These words are often very precise compared to our modern vocabulary, and a great deal of work was done by Margaret Gelling and Ann Cole in the late twentieth century to work out the specific meanings of many landscape terms. For example, the Old English word wæsse was thought to mean ‘marshy, wet place’, but Gelling realised that it was actually pointing to very particular. A wæsse is a place which is subject to flash-floods that happen quickly and disappear just as rapidly. Buildwas in Shropshire suffers such flooding (see the photographs), as does Alrewas in Shropshire.

Many more examples and photographs from Gelling and Cole’s fieldwork can be viewed online.

The importance of the English Place-Name Survey

These are just a few examples of how place-names can be used as evidence for language use, for settlement, for administration and for landscape history. The English Place-Name Survey collects that evidence and makes it available in a reliable and authoritative form for the use of researchers in a range of different subject areas.